CONSOLIDATED PBY / Catalina / Canso History

A brief PBY History by: John Clement

Development

The plane that would become the PBY Catalina was designed by Consolidated Aircraft Corporation’s lead designer, Isaac Machlin (“Mac”) Laddon when, in 1933, the United States Navy, wary of Japan’s growing influence in the Pacific Ocean, requested competing prototype designs for a flying boat with a range of 3,000 miles and a cruising speed of 100 mph to patrol Pacific seas in search of hostile navy forces.

Flying boats were the dominant long-range aircraft of the day in that they did not require runway construction. Laddon was able to draw on Consolidated experience building two previous flying boats for the Navy.

The XPY-1 Admiral, in 1928, was the first US Navy monoplane flying boat and featured an open cockpit and two engines mounted on struts between the wing and the fuselage and the P2Y, which made its maiden flight in 1932, had a closed cockpit and engines built into the leading edge of the wing which significantly reduced drag but it was under powered and lacked the range and payload required.

The XPY-1 Admiral, in 1928, was the first US Navy monoplane flying boat and featured an open cockpit and two engines mounted on struts between the wing and the fuselage and the P2Y, which made its maiden flight in 1932, had a closed cockpit and engines built into the leading edge of the wing which significantly reduced drag but it was under powered and lacked the range and payload required.

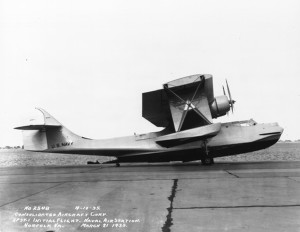

Both Consolidated Aircraft Corporations XP3Y-1 and Douglas Aircraft XP3D-1 prototypes met the US Navy design contest  criteria, but, at $90,000.00 per aircraft, the Consolidated design, XP3Y-1, which made its maiden flight on 21 March, 1935, was significantly less expensive.

criteria, but, at $90,000.00 per aircraft, the Consolidated design, XP3Y-1, which made its maiden flight on 21 March, 1935, was significantly less expensive.

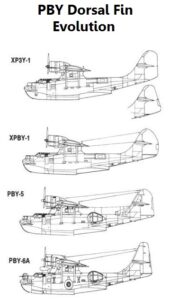

Further testing resulted in design adjustments to modify the vertical tail structure and dorsal fin (See image below) to prevent the tail from becoming submerged on takeoff and to upgrade the aircraft from “Patrol” to “Patrol Bomber” status.

The first flight of the modified XP3Y-1 in October, 1935, set a record for non-stop distance flight of 3,443 miles for a Class “C” seaplane from Cristobal Harbor, Panama Canal Zone, to Alameda, California in 34 hours 45 minutes. A flight which did reveal the need for more powerful engines. After the power-plant update, the plane was re-delivered to the Navy as XPBY-1 (PB for Patrol Bomber; Y for Consolidated in accordance with the US Navy aircraft manufacturer’s designation system).[1]

Classified by Consolidated as Model 28, production models from PBY-1 to PBY-3 were incrementally upgraded to enhance performance. PBY-4, designed to continue the pattern of gradual improvement with Pratt and Whitney 1,050hp radial engines, would, over its production run from May, 1938 to June, 1939, mark a great leap forward.

In a few later production models of the PBY-4, Plexiglass blisters which replaced the sliding hatches over the waist guns would become standard on subsequent models. They enhanced the gunners’ view of the enemy but also served as perfect observation posts for spotting enemy surface vessels.

The PBY-5 flying boat did not have wheels but they could be rolled onto land for maintenance using beaching gear, light duty wheels and struts that had to be installed by crew members in swim suits and removed once they had been rolled into the water once again.

But, a proper landing gear was required to transform the PBY Catalina to a truly amphibious aircraft. The prototype, XPBY-5A BuNo 1245, made its debut in late 1939.[2]

A limited number of PBY-1 to PBY-4 models had been manufactured but by 1943 production of the PBY-5 for the US Navy alone exploded (flying boat, 684 built from September 1940 to July, 1943) and PBY-5A (amphibian, 802 built between October, 1941 and January, 1945). In addition, production included aircraft for the RCAF, RAF, RAAF, and Dutch MLD.

The PBY had been manufactured by Consolidated plants in the United States at Buffalo New York, San Diego California and New Orleans. To meet the demand for the pby-5 and pby-5A, Boeing Aircraft of Canada, with a plant near Vancouver, and Canadian Vickers at St. Hubert, later Cartierville Airport near Montreal, were licensed to produce PBY’s. Boeing’s were coded PB2B; the Vickers planes were PBV.

The Soviet Union began receiving Catalina’s under Lend-Lease and producing their own under licence before World War II. The Soviet Aircraft were designated GST (Gidrosamolet transportnii/seaplane transport).

The final Consolidated PBY model, PBY-6A, appeared at the end of the war, manufactured from January 10 to May, 1945.[3]

One final wrinkle in the development of the aircraft. At about the same time that the PBY-5 and PBY-5A went into production, the US Naval Aircraft Factory designed a variant known as the PBN-1 Nomad, a larger and more rugged plane with greater range and stronger wings permitting a 2,000 pound (908 kg) increase in gross takeoff weight.

138 of the 156 Nomads produced at the Naval Aircraft Factory were delivered by air to the Soviet Union. The remaining 18 were assigned to training units at NAS Whidbey Island and the Naval Air Facility in Newport, Rhode Island. Elements of the Nomad design were incorporated in the PB2B-2 and PBY-6A.

Design Features

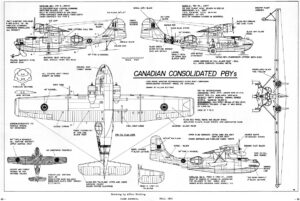

A two-step hull with a streamlined upper fuselage was attached to a parasol wing on a pylon braced by one pair of struts on each side running from the side of the hull to a position just outside the engines. This design permitted views of the ocean below unobstructed by the wing.

PBY Drawing courtesy of Al Botting

The pylon served as the flight engineer’s post with just enough room for the engine control panel, two windows through which each engine could be checked for oil leaks, and a seat raised to leave room below for other crew members.

Aft of the wing was a cabin with two bunks and a small galley.

The huge wing, 104 feet in length, was both the fuel tank that gave the PBY superior range and endurance and a strong lifting surface that gave the plane a 15,000 lb./6,600 kg payload.[4]

A no nonsense continuous I-beam spar and internal bracing contributed to wing strength. The pylon put the wing-mounted engines well above spray height since water can damage propeller tips moving just below the speed of sound.

The engines were mounted close to the fuselage to facilitate operation with one engine which increased range on long patrols but reduced the plane’s manoeuvrability on water and made it a very noisy machine to fly. [5]

A towering vertical stabilizer surface aided maneuvering on water as well as in the air.

Floats to keep the wingtips out of the water on takeoff and landing were retractable, swinging out and upward to morph into the wingtips when the craft was airborne.

Four bomb racks, two on the underside of each wing, could carry a total of four thousand pounds of bombs, depth charges or torpedoes.

Photo taken in the flight engineer’s station within the pylon shows the instrument panel

and small windows, left and right, through which the engines could be checked for oil leaks.

The result was the most aerodynamic flying boat ever designed and the most-built flying boat of World War II with a production run of about 3,305. [6]

Construction was all-metal, stressed skin aluminum sheets riveted to an aluminum frame, except the ailerons and wing trailing edge which were fabric-covered to reduce the weight of the aircraft. The fabric, unbleached cotton, was hand sewn and the seams sealed with varnish to make them water tight and add rigidity. Rivets were kept in a freezer before being driven into place to make all joins especially tight when the rivets expanded in warming to room temperature.

Many aviation experts considered the PBY obsolete when the war started.

In Combat

Unobstructed view of ocean and land targets, rugged construction, long range, high payload, the PBY provided a strong military performance platform. High speed? No, but its speed was more than adequate for maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare. “Without her crew the plane is but an inanimate object, unable to move, express itself or show off her incredible characteristics. But…together with her crew they showed the world through their collective efforts the PBY’s contribution to aviation.”[7]

It’s time now to look at what the PBY and her crews were able to do.

Catalina’s served in the wartime armed forces of the U.S.A., Canada, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, the Soviet Union, the Netherlands, Free France and Brazil. With the United States being neutral until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941. The first PBY’s to enter combat in World War II were flown by Britain and her allies.

PBY Catalina’s in the Royal Air Force

In 1939, the Royal Air Force (RAF), ordered a single example of a commercial model of the PBY-4 flying boat for an evaluation which was still in progress when war was declared and a decision was made to order the aircraft in large numbers for military service. The first of about 700 Consolidated flying boats entered service in early 1941 with 209 and 240 Squadrons of Coastal Command. Many of the later aircraft were diverted to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF).

The RAF favoured flying boats for their longer range but did have to accept twelve PBY-5A aircraft (designated Catalina IIIA) under Lend-Lease. True to its tradition of shunning alphanumeric designations, the RAF named their PBY’s Catalina’s, a name adopted by the US Navy in October, 1941. Consolidated president Reuben Fleet may have suggested the name “Catalina”, to the RAF as this was the name of an island off the coast of California not too far from the Consolidated plant.

The Catalina’s Hollywood moment occurred on 26 May 1941 when an RAF flying boat based in Northern Ireland and co-piloted by Ensign Leonard B. Smith of the US Navy, spotted the German battleship Bismarck as it attempted to reach occupied France for repair, thus initiating the process that would see the destruction of Germany’s largest battleship.[8]

Ensign Smith’s involvement was kept secret because of the official neutrality of the United States.[9]

On 17 July 1944 RAF officer John Cruickshank, piloting a Mk IV PBY Catalina JV928 from the Shetland islands, came under heavy anti-aircraft fire from German Submarine U-361. Seriously wounded, Cruickshank pressed home the attack and sank U-361 on his second pass. He was awarded the Victoria Cross and is the last living recipient to have been awarded the VC during the Second World War.

PBY Catalina’s and Canso’s in the Royal Canadian Air Force

The first PBY aircraft taken on strength by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) by No. 116 Squadron at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia on 28 June 1941,were nine Catalina Mark I flying boats diverted from an RAF contract to fulfill a request from the AOC (Air Officer Commanding) A/C (Air Commodore) A.E. Godfrey.[10]

Some flying boats were stationed on Canada’s east and west coasts for maritime patrol and convoy escort but, unlike the RAF, the RCAF favoured the amphibian PBY-5A for their Canadian squadrons since using straight flying boats was impractical during Canadian winters.

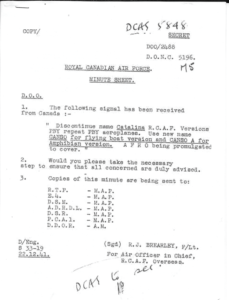

In December, 1941, the decision was made to rename PBY-5A aircraft built in Canada for the RCAF because specifications for their Canadian built models were different from British and American versions.

Canadian Government PBY-5 and PBY-5A naming edict

The name, “CANSO,” was chosen for the Strait of Canso located in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada dividing the Nova Scotia peninsula from Cape Breton Island. The RCAF’s non-amphibious aircraft were to be named “Canso” while the amphibians were known as “Canso As”. The Catalina’s loaned from the RAF retained their original British name.[11]

The figures reported in the next paragraph indicate that no “CANSO” flying boats meeting RCAF specifications, were built. The number of Catalina’s and Canso’s taken on strength by the RCAF in WW II were 30 ex RAF Catalina flying boats and 208 Canso A amphibians.[12]

The two RCAF overseas squadrons, 422 and 413, flew Catalina’s supplied by the RAF. No. 422 (GR/General Reconnaissance) Squadron, based at Lough Erne, Northern Ireland on 2 April 1942, ferried key personnel and equipment to northern Russia. In transit they patrolled the route of Russian convoys watching for submarines and surface raiders operating off the coast of Norway.

By March, 1942, Japan seemed to be on an inexorable march to supremacy in the Western Pacific and the South China Sea. Since the destruction of Pearl Harbour by a Japanese aircraft carrier fleet on December 7, 1941, Japan had overrun Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, and Burma. A carrier-launched air raid destroyed the northern Australian port city of Darwin. Next up, the Indian Ocean where defeat of the British Eastern Fleet would have had disastrous consequences for the allied forces confronting the Axis powers.

“The most dangerous moment of the war, and the one which caused me the greatest alarm, was when the Japanese fleet was heading for Ceylon and the naval base there. The capture of Ceylon, the consequent control of the Indian Ocean, and the possibility at the same time of a German conquest of Egypt would have closed the ring and the future would have been black”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill

The British fleet based in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was a mix of modern and older vessels cobbled together in haste and put under the command of Admiral Sir James Somerville who realized his only option against a superior force was to adopt a defensive stance which involved keeping his ships out of port except for refueling and taking on food and water.

His plan was to concentrate his fleet outside the range of Japanese reconnaissance aircraft during daylight and close in at night. The British could use their radar-equipped Albacores to slow the Japanese fleet enough for their battleships to engage in the dark. Stay out of range they did but the British fleet never launched an offensive against the Japanese fleet. The fleets never met.

The Japanese expectation was for complete surprise which would find Royal Navy ships confined to harbour as had happened at Pearl Harbour and Darwin. Somerville’s overarching challenge was to locate his adversaries to eliminate the element of surprise.

Cue the Catalina’s.

The RCAF’s second overseas squadron equipped with Catalina flying boats, No. 413 (GR) Squadron, was formed and stationed in Scotland before being sent to Ceylon in late March, 1942, to supplement RAF Catalina’s on the island.

Voices from the Past

On 4 April, 413 Squadron leader Leonard Birchall took off in Catalina QL-A on a reconnaissance patrol of the sea south of Ceylon. At about 4pm, after 10 hours in the air, Birchall sighted a smudge on the southern horizon. Investigating from a height of 2000 feet, he saw the Japanese fleet formation including carriers, battleships, escorts and supply ships.

Turning north under full power, it was already too late for the Catalina and its crew. The Catalina’s radio operator managed to get off a sighting report. But before he could finish his regulation two repeats, cannon shells from Japanese fighters began to rip through the air-frame – demolishing the radio. The fight lasted just seven minutes. Some 350 miles from land, with dusk settling in, Birchall was forced to put his Catalina down in the ocean. The single transmission was, fortunately, enough. It was received – though somewhat garbled – and rapidly shared among Ceylon’s defenders.

“We were saved from this disaster by an airman on reconnaissance who spotted the Japanese fleet and, though shot down, was able to get a message through to Ceylon which allowed the defending forces there to prepare for the approaching assault; otherwise they would have been taken by surprise.”

Sir Winston Churchill

Birchall and five other survivors were taken aboard the Japanese destroyer Isokaze where they were beaten and interrogated and ultimately sent to a prison camp for the duration of the war, surviving it. [13]

Royal Canadian Air Force Squadron Leader Leonard Joseph Birchall, the “Saviour of Ceylon”

Among RCAF squadrons flying Canso A aircraft, No. 162 (BR) Squadron was the most successful anti-submarine squadron during the second world war with five U-boats destroyed, one shared sinking and one U-boat damaged. This was due to the skill and courage of the crews but also to location.

Formed at Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, on 19 May 1942, it was seconded to RAF Coastal Command in January, 1944, and stationed first at RAF Reykjavik, Iceland, relatively close to U-boat routes from Norway into the North Atlantic. In May, 1944,162 was moved to Wick on the northeast coast of Scotland to intercept enemy submarines leaving Norwegian ports just before and then after the Normandy invasion.

The North Sea between Britain and Norway is an even smaller body of water than that east of Iceland and this, along with German urgency to dispatch U-boats to the English Channel following D-Day on 6 June 1944, probably accounted for the frequency at which U-boats were spotted and attacked by 162 Squadron. [14]

Flying from Reykjavik:

-

F/O C.C. Cunningham

and crew attacked a U-boat but could only claim it as damaged. -

April 17,F/O T.C. Cooke and crew scored the squadron’s first kill when they sank U-342.

Sorties launched from Wick:

-

June 3, F/L R.E. McBride and crew sank U-447

-

June 11, F/O L. Sherman and crew sank U-980

-

June 13, W/C Chapman and crew sank U-715. Also on this day, F/O Sherman sighted and attacked a U-boat but was shot down.

-

June 24, F/L D.A. Hornell and crew sank U-1225

-

June 30, F/L McBride attacked U-478 but the depth charges failed to release. An RAF Liberator was called in and sank the sub.

F/L D. A. Hornell’s attack on 24 June 1944, earned him the Victoria Cross, awarded posthumously. On sea patrol in the North Atlantic Hornell’s aircraft was fired on and badly damaged by U-1125. Nevertheless, he and his crew succeeded in sinking the submarine. Hornell then managed to bring his burning aircraft down on the heavy swell. There was only one serviceable dinghy which could not hold all the crew so they took turns in the cold water.By the time the survivors were rescued 21 hours later, Hornell was blinded and weak from exposure and cold. He died shortly after being picked up. Hornell was laid to rest in Lerwick Cemetery, Shetland Islands.[15]

Author’s note:

A writer faces a difficult decision in choosing to feature individual achievements such as those of John Cruickshank, Leonard Birchall and David Hornell. World War II military personnel served their countries well and many, many people were called upon to do extraordinarily courageous things. Deep gratitude is owed to all veterans of that horrific conflict.

John Clement

And finally, the Canso A history you will not find anywhere else. The writer’s father flew Canso’s with the RCAF from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and Torbay, Newfoundland.

Initially posted to 160 Squadron as a 2nd officer/co-pilot, he was selected for training to qualify as a first officer/captain and was posted to # 3 Operational Training Unit, Patricia Bay, where he flew RCAF 11024 now restored to airworthiness by volunteers of The Catalina Preservation Society and renamed “Shady Lady.”

Training included night landings on the water. The only guide was a line of light buoys anchored in the bay with the other end tied to a boat. The boat’s role was to keep the line taut, directed into the wind. At night, the water was black and the shore was black. With no visual reference other than the string of lights, the pilot had to land on instruments, the artificial horizon and the altimeter.

To prevent the pilot being distracted from the instruments by glancing out the window, at a certain point in the approach the pilot’s seat was lowered so he couldn’t see outside. Training completed, he returned to 160 Squadron as a captain.

No. 160 Squadron Canso’s flying over the Atlantic carried homing pigeons. If an aircraft went down without being able to radio its position, the position could be written on a slip of paper which was to be attached to the bird’s leg and the pigeon released to fly back to the airfield. On every flight the pigeon master sent along the designated emergency pigeon plus a pigeon or two in training. The pigeon cadets were to be released when the plane was a certain distance from the airfield. The pigeons, kept in cages on a shelf in the galley, were not to be fed. The crew fed them bits of toast.

A way had to be found to release the pigeons so they wouldn’t be injured or killed by the back draft from the propellers. The solution was to put the bird in a brown paper shopping bag with the top loosely tucked in. The pigeon, in the paper bag, was put out one of the waist gunners’ blister windows and thrown down to keep it away from the plane’s propeller back-wash and the tail structure. The bag tumbled in the wind until it opened and the bird found its way out and began its flight back to the airfield.[16]

PBYs in the United States Navy and the United States Army Air Force

On December 27, 1941, America’s first offensive airstrike of the Pacific War turned out to be a textbook example of how not to use the PBY Catalina in combat. Six PBY’s took off from Ambon Island in the Dutch East Indies to bomb a Japanese base at Jolo in the southwest Philippines. The Catalina’s were the only aircraft with the range to make the 1,600 mile round trip. Four of the six were shot down and in his post-action report one of the surviving pilots wrote,

“It is impossible to outrun fighters with a PBY-4. Under no circumstances should PBY’s be allowed to come in contact with enemy fighters unless protected by fighter convoy.”

An observation from a PBY Pilot

It was no secret that the PBY’s cruise speed was 125 miles per hour. Perhaps the desire to retaliate after Pearl Harbour clouded the judgment of the commanding officer but after that inauspicious start the PBY distinguished itself in the Pacific as it had done in other theaters of war.

During the Guadalcanal Campaign PBY’s painted matte black were so effective in carrying out night bombing, torpedoing and strafing missions that they became a standard part of the US Navy’s battle plan. The fourteen Black Cat squadrons flying slowly at night, dipping to ship mast height, sank or damaged thousands of tons of Japanese shipping as well as bombing and strafing land based Japanese installations.

Particularly in the Pacific, air-sea rescue PBY’s, flown by the United States Army Air Force and nicknamed “Dumbos” from the original Walt Disney movie that was released during the war, retrieved thousands of downed pilots and shipwrecked seamen. The bunks proved especially valuable on search and rescue missions.

The use of Catalina bunks in a rescue situation.

PBY’s and their crews were very effective in attacking enemy forces directly but their greatest contribution to the war effort was arguably as lookouts.

“…the same phrases reappear in accounts of nearly every WWII naval battle, Atlantic and Pacific: “A PBY spotted the carrier…While Catalina’s shadowed the fleet through the night…As the PBY followed the phosphorescent wakes …When the fog suddenly lifted, the PBY saw the picket destroyers…”[17]

The most significant American PBY discovery of enemy intent: the sighting of the Japanese fleet racing toward Midway.

PBYs in the Royal Australian Air Force

In Australia, “It is often said that the Consolidated PBY Catalina’s were to Australia what the Supermarine Spitfire was to Britain.”[18]

With a Japanese invasion a very real threat early in the war, RAAF Catalina coastal patrols and missions into the Solomon’s were crucial, and when the Allies soon went on the offensive, Aussie Cats ranged as far as the coast of China, mine-laying and night-bombing. It’s said that when the RAAF Catalina crews ran out of bombs, they threw out beer bottles with razor blades inserted in the necks. The bottles whistled as they fell in the dark, which was designed to frighten the Japanese.[19]

From June 1943 to July 1945, Qantas operated flights from Perth to Ceylon, duration up to more than 32 hours, dubbed the “flight of the double sunrise.” These flights carried a maximum of 3 passengers; it was clear that PBY’s were not in a position to be part of the long distance passenger flights that developed in post-war years.

PBYs in the Royal New Zealand Air Force

Fifty-six Catalina’s were operated by the Royal New Zealand Air Force between 1943 and 1953 at an Operational Training Unit in New Zealand and with operational squadrons at various points throughout the Pacific in anti-submarine warfare, shipping escort, air-sea rescue and transport roles. They continued to be operated after World War II because they filled a vital role in South Pacific communications.[20]

Like New Zealand, many countries continued to use PBY’s in their Air Forces for non-combat roles such as air/sea rescue and transportation. The last Catalina in U.S. service was a PBY-6A retired from use on 3 January 1957.[21]

The last Canso in the RCAF, 11089, was retired from service at Downsview on 08 April 1962 and went into civilian service as CF-PQO after being struck off charge on 29 November 1962[22]

PBYs in Soviet Union Forces

“The Catalina in the Soviet Union was used to carry out a wide range of tasks, from search and rescue operations to anti-submarine missions and everything in between.”[23]

PBYs in the Brazilian Air Force

The Brazilian Air Force flew Catalina’s in naval air patrol missions against German submarines starting in 1943 and also air mail deliveries. In 1943, German submarine U-199 was sunk off the Brazilian coast by a coordinated Brazilian and American aircraft attack.

The Brazilians continued to operate military Catalina’s on humanitarian supply flights to outlying settlements in the Amazon area until 1982.

Civilian Roles

Very few PBY-5 flying boats outlasted the war but amphibious PBY-5A models have flown to the present day. In civil aviation the crew dropped to two with the relocation of the engineers engine control panel from the pylon to the cockpit.

Many PBY’s that survived to post war went on to serve on African Safari’s and Canadian fishing charters.

Some surplus PBY’s were converted to flying yachts for the wealthy. Jacques-Yves Cousteau used a PBY-6A to support his diving expeditions.

The Catalina Preservation Society monitors PBY restoration projects around the world. Out of a total production of about 3,305 there are about fifteen airworthy PBY-5A in the world today (2021).

Now that may not seem like a lot until one considers that of the more than 18,000 World War II B-24 Liberator bombers produced by Consolidated and its licensees, only 3 are airworthy today.

PBY’s are still flying because they have not outlived their usefulness, particularly as water bombers. The Catalina Preservation Society “Shady Lady” being a case in point.

Not bad for an airplane deemed obsolete in 1939

Post Script:

The photo below is of the writer’s father, F/L George Clement, and the crew of an RCAF Canso A. F/L Clement is at the far left of the back row. The pigeons were confined to their coop when the photo was taken.

Acknowledgements

Sue McTaggart’s proofreading and editing of an early draft improved my writing. Bob Dyck corrected a comment on Canso handling characteristics that I’d taken from an online site thus preventing me from exposing my absolute ignorance of what it’s like to fly the aircraft. David Legg’s comments proved invaluable in correcting errors in online sources that I’d consulted and adding information that I’d missed, especially the distinction between Canso and Canso A aircraft in the RCAF. The warm receptions of snippets of my father’s story by Sue McTaggart, Derwyn Ross and Ian Scanlon were reassuring. Derwyn initiated the whole process when he asked for a volunteer to take on the task of rewriting the History section of The Catalina Preservation Society’s web site. His comments on the first draft helped me to clarify themes and emphasis that guided me to focus on the story of the aircraft brought to life by the crews who flew her. My heartfelt thanks to you all.

John Clement, December, 2021.

Citations

[1]Creed, Roscoe, PBY -The Catalina Flying Boat, Naval Institute Press, 1985.

[2]https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Consolidated_XPBY-5A_BuNo_1245_Dec_1939.jpgClick on “File.” “Navy’s new ‘mystery’ plane…”

[3]For a video tour of a PBY-6A, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GOjE-_cI-K8&t=1091s

[4]The wing was the first “wet” wing on a production airplane, containing the fuel without bladders thus reducing weight by half a pound per gallon of fuel.

[5] As years go by, many Canso pilots report degenerative hearing loss with captains affected in their left ears and first officers in their right.

[6] Calculated by David Legg of The Catalina Society of the United Kingdom.

[7] Derwyn Ross, The Catalina Preservation Society.

[8] For a complete account of The Bismarck, go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_battleship_Bismarck

[9] Smith was one of nine American officers assigned to the RAF as special observers. Smith was the first American to participate in a World War II naval victory[2] and is sometimes considered the first American to be directly involved in World War II for his actions.

[10] A. E. Godfrey was a remarkable Royal Canadian Air Force officer. On Sept. 22,1943, then Air Vice Marshall Godfrey became the most senior Canadian officer to fire directly on the enemy during World War II. For the full story go to https://legionmagazine.com/en/2005/05/godfrey-of-the-rcaf/

[11] RCAF document dated December 22, 1941 generously shared by David Legg, Editor: The Catalina News, The Catalina Society. https://www.catalina.org.uk

[12] David Legg, The Catalina Society, https://www.catalina.org.uk.

[13] RAF pilot Flight Lieutenant Graham, sent to followup on Birchall’s sighting, also found the fleet. His plane, Catalina Z2144, was shot down. No survivors.

[14] Finding a U-boat was not a totally random process. Once every 24 hours, each U-boat had to extend its radio antenna above water to signal its position to Admiral Karl Dönitz, the commander of the U-boat fleet. Using shore-based receivers and triangulation the allies could track the U-boat radio signals as they left their Norwegian ports.

[15] For more, go to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Ernest_Hornell

[16] For a list of all RCAF Canso and Catalina squadrons during World War II, go to https://www.cansofunds.com/the-canso-and-the-catalina-in-the-r-c-a-f/

[17] https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/08/31/cat-tales-the-story-of-world-war-iis-pby-flying-boat/

[18] https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/catalinas-in-the-pacific

[19] https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/08/31/cat-tales-the-story-of-world-war-iis-pby-flying-boat/

[20] https://www.nzcatalina.org/history

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consolidated_PBY_Catalina

[22] David Legg, The Catalina Society, https://www.catalina.org.uk

[23] https://vvsairwar.com/2017/03/07/the-soviet-pby-catalinas-of-wwii/

Photograph Credits

A – RCAF 11024 A deep gratitude to Professional Aviation Photographer Heath Moffatt for allowing TCPS use of this image

B – xp3y-1 http://www.shu-aero.com/AeroPhotos_Shu_Aero/Aircraft_C/Consolidated/XPY_1_01.html

PBY Variants:

Model 28 – Base Prototype Model Designation

XPY-1 Admiral

The Consolidated XPY-1 Admiral, was a modern design for the day, and, the beginning of flying Boat designs that would eventually lead to the PBY, arguably the most successful fly boat ever built.

XP3Y-1 – Prototype Model Designation

PBY-1 – Model 28-1

September 1936 – June 1937

Initial Production Model featuring improved and more powerful R-1830-64 900hp engines; 60 produced.

PBY-2 – Model 28-2

May 1937 – February 1938

Modified United States Navy Model with alterations to the empennage and hull reinforcements: 50 produced

PBY-3 – Model 28-3

Fitted with R-1830-66 1,000hp engines, 66 produced.

PBY-4 – Model 28-4

Integrated the recognizable fuselage “blister” gun positions; name “Catalina” after the Catalina Island off the San Diego Coast is utilized for the series; fitted with R-1830-72 1,050hp radial engines, 33 produced.

PBY-5 – Model 28-5

R-1830-82 or R-1830-92 radial engines capable of 1,200hp; export version for UK, Dutch East Indies, Australia and Canada; Tricycle landing gear testing implemented and integrated to final PBY-5 production models making the system completely amphibious; general improvements throughout.

XPBY – 5A

One PBY-4 converted into an amphibian and first flown in November 1939.

PBY-5A – Model 28 – 5A

Full Amphibious Variant with two 1,200 hp R-1830-92 engines, first 124 had one 0.3in bow gun, the remainder had two bow guns; 803 built including diversions to the United States Army Air Corps, the RAF (as the Catalina IIIA) and one to the United States Coast Guard: 761 produced.

PBY-5B – Improved Model of the 5A

Mk I – RAF Coastal Command Designation of the PBY-5 model series.

PBY-5 – PBY-5A Canso – Canadian designation from December 1941 of the PBY model series as produced by Canadian Vickers in Cartierville Quebec and Boeing of Canada in Vancouver BC.

PBN-1 “Nomad” – Naval Aircraft Factory model with taller fin and rudder systems; aerodynamic and hydrodynamic improvements to airframe.

PBY-6A – PBY with search radar installed.

OA-10B – United States Air Force Designation of the PBY-6A.

GST – Model Designation of PBY series as produced by the USSR.